(formerly Gilgil Baboon Project 1971-1984)

The research on the social behavior and ecology of a population of wild baboons began in 1971. The troop under study, the Pumphouse Gang, lived in a high-elevation savanna as part of a diverse wildlife community on a 45,000-acre cattle ranch in the middle of Kenya's central Rift Valley.

Initially, the research resulted from overlapping doctoral projects done by graduate students from the University of California, Berkeley (Harding, Malmi, Strum). Then in 1976, the Gilgil Baboon Project was created to provide important continuous project records on key demographic and social variables. Dr. Shirley C. Strum (Professor of Anthropology, University of California, San Diego) has been director since 1976.

The Project has hosted graduate students from the United States, UK, Europe and Kenya. We were the first primate research project in Kenya to use local research assistants and trained them as para-behaviorists, para-ecologists, and conservationists.

Basic Research 1972-1984

Dr. Shirley Strum recording behavior at Gilgil; photo by Neil Leifer.

The focus of research during the first 8 years was on important scientific issues related to baboon socio-ecology. For example, Strum’s research included:

- Social networks, social roles and social dynamics (1972-1974)

- Predatory behavior of olive baboons (1972-1974, 1975)

- Consistency and stability of social networks (1975)

- Conflict and resolution in the transition to adulthood among adolescent male baboons (1976-1977)

- Bio-social parameters in a population of olive baboons: genetics and consequences of capture and release on social relationships (1978-1979)

The project was the cover story in May 1975's National Geographic:

Conservation 1980-1984

However, changes in the context of the baboons - such as different land tenure and land use - catapulted the Gilgil Baboon Project into conservation work. Initially this was to find ways to reduce conflict between the baboons and their human neighbors, now farmers, over crops.

Thus began two decades of conservation work based on two principles:

- Develop and use the best scientific evidence in the solution of primate conservation problems;

- Work with the local community in finding the solutions and implementing “community-based conservation.”

The first challenge was how to stop the baboons raiding the farms that had recently been established in the baboons’ traditional home range. The first step was to study the development of crop-raiding behavior in a population of olive baboons that had not been raiders before and not all of whom took up the raiding lifestyle.

Although the work was carried out from 1981 to 1984 it is still the only data that documents the comparative costs and benefits as the animals themselves change their behavior. In addition we tested traditional techniques such as guarding and chasing to determine their effectiveness as well as new techniques such as leopard dung, playback of baboon distress vocalizations, chili pepper applications and conditioned taste aversion (CTA).

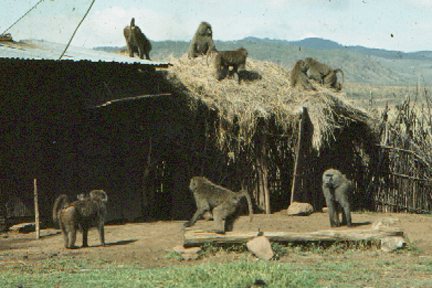

In addition, the Gilgil Baboon Project began working with the local community, first developing a “woolcraft” enterprise (photo, above). This involved teaching the crafts of spinning and dyeing wool yarn with natural dyes and then making wool carpets. We also helped build the first local primary school and set up educational activities related to conservation.

Despite good progress on all fronts, events overtook the Project (see Almost Human for details). The next phase of conservation research began with the translocation of 3 troops of baboons from their traditional home 200 km to the northeast onto the Laikipia Plateau.

Baboons are not an endangered species, however these were scientifically valuable groups. The baboon experiment was the first scientific translocation of primates. The rationale was simple:

- In the process of trying to save these baboons, we could evaluate the feasibility of translocation as a conservation and management technique for primates.

- If the baboons, who are both great generalists and opportunists, did not survive the move, it was unlikely that other more specialized (and endangered) primates could.

- If the translocation was successful, it would yield important lessons and a model for future primate translocations.

Baiting the traps:

Moving one of the animals during the capture:

Releasing baboons at their new home at Chololo:

The success also depended on good relations with the local community understanding that in conservation problems, if people are part of the problem, people have to be part of the solution. We continue to be involved in community based conservation (CBC) including working with six local primary schools. The Project was renamed: Uaso Ngiro Baboon Project (UNBP).

Basic Research 1984-present

After translocation Strum’s/UNBP research included:

- Translocation of the pumphouse baboons: testing the social strategy hypothesis

- Social and ecological influences and consequences of adaptive shifts (1988-1989)

- Evolutionary payoffs of aggression, dominance and social strategies (1987-1992)

- The role of ecological and social complexity in the evolution of cognition in baboons (1993 to present)

- Baboon troop movements: cognition in the head or in the world (1995-2000)

- The costs and benefits of troop fusion (2000 to present)

- The role of individuals in troop movements (2008)

- The costs and benefits of shifting foraging strategies to Opuntia spp: relations with local troops, relations with local people, reproduction and mortality (2007-present)

- Pilot study on the stress of foraging decisions (2008)

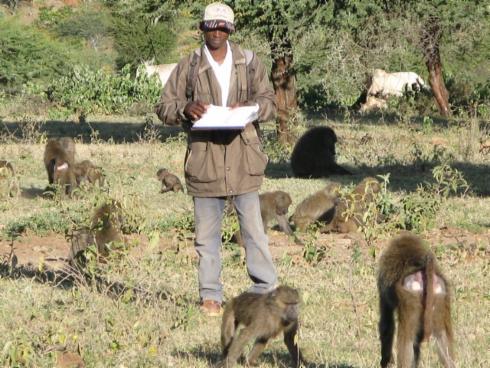

Ecological monitoring of the area where the baboons range has been a significant part of our research since 1981. Below, Patrick, one of the research assistants, takes daily data on the Pumphouse Gang.

UNBP has one of the best ecological data sets of any primate research project in Africa.

In partnership with African Conservation Centre (ACC), we are extending the scope of the monitoring as well as finding and coordinating previous data from other organizations relating to this area.

An exotic Opuntia cactus species (below) is rapidly invading the area between Doldol and Il Polei.

Above, a baboon eats the brilliant pink fruit. In 2007, UNBP began a major project to monitor and understand the factors that influence this invasion. These include livestock, people, baboons and elephants in addition to topographic and climatic factors.

See the Conservation pages for more about how UNBP has worked with the community on dealing with this invasive species, including ways the women's group and cultural center, Twala, may benefit financially.

###

UNBP and St. Andrews University formed a research and training partnership from 1985-1997. During that time graduate students from St. Andrews carried out doctoral and post doctoral studies under the auspices and with support from UNBP.

(See also the work of Robert Barton, Andrew Whiten, Frances Marsh, Deborah Custance, Thomas Sambrook, Robert Musyoki, Duncan Castles, Deborah Forster, Gerald Muchemi, Rebecca Frank, Heather Poje)